Disclaimer: “As someone deeply fascinated by the intersection of history and technology, I offer this exploration not as a historian, but as a curious observer. My aim is to weave the concept of enshittification—a term that captures the decline in quality of digital services—into the fabric of historical narratives, inviting readers to envision future generations’ perspective on today’s tech titans. Imagine, if you will, the day when the grandeur of Silicon Valley’s giants is likened to the quaintness of icehouses and horse-drawn carriages, relics of a bygone era. This piece concludes with a nod to the gaming industry, a sector ripe for comparison due to its ongoing evolution, though the final chapter of its story remains unwritten…”

Enshittification, a term coined to describe the pattern of decreasing quality in online services and products, has been a powerful force in shaping innovation throughout history. While the word itself may not be precisely appropriate, the concept it represents—the tendency of successful companies to become complacent, resist change, and ultimately face destruction at the hands of more innovative competitors—has been a recurring theme in the story of progress. From the rise and fall of the ice harvesting industry to the disruption of traditional transportation by visionaries like Cornelius Vanderbilt, history is replete with examples of how the refusal to adapt can lead to the downfall of even the most powerful enterprises.

In today’s rapidly evolving technological landscape, the lessons of history are more relevant than ever. As online platforms and services become increasingly central to our lives, the risk of enshittification looms large. Companies that once revolutionized their industries now face criticism for their declining quality and lack of innovation. Meanwhile, new players, unencumbered by the baggage of legacy business models, are emerging to challenge the status quo, just as Vanderbilt did with the railroads and Tudor did with the ice trade.

Horses: Manure and Mobility Industry

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the problem of horse manure was a pervasive one, affecting major cities across Europe and North America. The most literal example of this issue was highlighted in an episode of the TV series ‘Silicon Valley,’ where the character Jared Dunn drew a parallel between the impact of PiedPiper on the Internet and the effect of the automotive industry on horses.

In London, by the late 1800s, there were 50,000 horses working daily, each producing 15-35 pounds of manure and around 2 pints of urine per day. This led to streets attracting flies and spreading diseases like typhoid fever. The situation was so dire that in 1894, The London Times predicted that within 50 years, the city would be covered in 9 feet of manure.

In 1890, there were 13,800 carriage manufacturer companies in the United States. However, just thirty years later, in the 1920s, only 90 remained. With the surging demand for automobiles, economic decline, and a stubborn denial of the changing times, companies accepted their fate and refused to seek alternatives.

Vanderbilt, on the other hand, demonstrated foresight. Initially investing heavily in horse-drawn ferries, he recognized the disruptive potential of railroads and automobiles when they emerged in the early 20th century. Vanderbilt boldly (and sometimes illegally) pushed forward, transitioning his investments into this new mode of transportation. He understood that laws and the status quo were inhibiting progress, so he built a railroad empire, paving his way to join the Illuminati (probably).

Of course, money eventually corrupted the Vanderbilt family, but the idea stands: companies that fail to adapt and keep innovating will likely face disruption themselves. Just like the horse-based businesses that focused on short-term profits by squeezing their “locked-in” customers, modern tech companies that allow their products to stagnate and degrade may find themselves vulnerable to new upstarts offering a better user experience.

The horse industry’s resistance to automobiles, through political lobbying and fear-mongering rather than innovation, mirrors the behavior of modern tech giants trying to lock in users and lock out competition. In the early 1900s, the “carriage lobby” in some states went to great lengths to hinder the adoption of automobiles, such as requiring car drivers to hire a person to walk in front of the vehicle waving red flags to prevent horses from being frightened. However, history has shown that this strategy was not sustainable, as horse-based businesses that failed to adapt were swiftly wiped out once the superior technology of automobiles became widely available.

In both cases, business models built around an increasingly obsolete technology can experience significant short-term growth by exploiting their captive customers. However, by allowing their products and services to deteriorate, they ultimately sow the seeds of their own disruption and collapse. Just as the giants of the horse industry fell, modern tech companies that succumb to “enshittification” may find themselves rendered irrelevant by new innovations they failed to embrace.

The businesses that will endure are those with the vision to relentlessly pursue innovation, even if it means creatively destroying their own profitable legacy businesses. Clinging to the past by abusing your current customers inevitably leads to those customers abandoning you entirely when something better comes along.

Most of the horses were probably slaughtered.

Ice Harvesting: Ice belongs to the Wealthy!

Before the advent of refrigeration, ice harvesting was a booming industry that played a crucial role in preserving food and cooling drinks. During the winter months, workers would cut large blocks of ice from frozen lakes and rivers, storing them in icehouses for use throughout the year. At its peak in the late 19th century, the United States alone harvested over 25 million tons of ice annually, employing tens of thousands of workers.

The ice harvesting industry was dominated by powerful companies and wealthy individuals who controlled the icehouses and distribution networks. Frederic Tudor, known as the “Ice King,” was one of the most prominent figures in the industry. Tudor built a vast empire by shipping ice from New England to the southern United States, and even as far as India and the Caribbean. His innovative insulation techniques, using sawdust and hay, allowed him to transport ice over long distances without significant melting. Tudor’s success inspired many others to enter the industry, leading to fierce competition and substantial profits for those who controlled the supply chains.

However, the introduction of the first practical electric refrigerator for home use in 1913 marked the beginning of the end for the ice harvesting industry. As electric refrigerators became more affordable and widespread in the 1920s, they offered a more convenient and reliable way to preserve food, making the labor-intensive and weather-dependent ice harvesting industry increasingly obsolete.

Despite the clear advantages of electric refrigeration, many in the ice harvesting industry were reluctant to accept the impending disruption. Companies and individuals who had profited immensely from ice harvesting were hesitant to invest in or adopt the new technology, believing that natural ice, with its long history and established infrastructure, would continue to be in demand. This resistance to change was exemplified by the Knickerbocker Ice Company, one of the largest ice harvesting firms in the United States. The company continued to invest heavily in ice harvesting operations and infrastructure, even as electric refrigeration gained popularity.

As electric refrigeration became more widespread, the demand for natural ice plummeted. By the 1930s, the once-thriving ice harvesting industry had all but collapsed. Many of the formerly profitable icehouses were abandoned, and the companies that had refused to adapt were either forced out of business or had to drastically downsize. The Knickerbocker Ice Company, for example, declared bankruptcy in 1932, a victim of its own resistance to change.

The decline of the ice harvesting industry serves as a powerful lesson in the importance of adaptation and innovation. Companies that prioritize staying ahead of technological advancements and are willing to disrupt their own profitable legacy businesses are more likely to thrive in the long term. Just as the ice harvesting industry was replaced by electric refrigeration, modern companies that fail to adapt may find themselves rendered obsolete by new technologies and business models.

In today’s rapidly evolving business landscape, the ability to anticipate and embrace change is more critical than ever.

Games Industry: Case of Vanilla Management

The games industry started in the same place where all good things start—someone’s basement or garage. I will never forget the experience of playing “Vampire: The Masquerade – Bloodlines” for the first time. Despite its flaws, the game had so much love behind it that it motivated hundreds of people to come together and make it the truly unique narrative it is today.

As the industry grew and the potential for massive profits became apparent, a new “vanilla CEO” mentality emerged among corporate executives. They were put in those seats to pursue vanilla goals, without a complete understanding of why the game industry grew from when I was ridiculed in middle school for playing games into one of the most mainstream things imaginable.

This shift in focus led to the rise of “live service” games, designed to extract a steady stream of revenue from players through microtransactions, season passes, and other manipulative mechanics. These games often capitalize on a small percentage of players (whales) who account for a disproportionate amount of revenue. This phenomenon was satirized in a 2014 episode of South Park, “Freemium Isn’t Free,” which showcased how mobile games profit from just 1% of their user base. Ironically, this isn’t an example of enshittification, as these mobile games are deliberately designed to be bad enough that a small financial investment seems worthy to avoid dealing with annoying elements.

The consequences of this profit-driven approach are far-reaching. Developers, once celebrated for their creativity and dedication, now find themselves at the mercy of corporate whims. Mass layoffs have become commonplace, with even highly successful studios like Tango Gameworks falling victim to the ruthless mandate of cost-cutting. In 2023, despite the critical and commercial success of “Hi-Fi Rush,” Tango Gameworks was cut to make place for an inferior game.

Similarly, Arkane Austin, known for critically acclaimed games like “Prey” and “Dishonored,” faced closure after the commercial failure of “Redfall,” a game heavily influenced by the live service model. This decision underscores how the industry’s focus on live service games can lead to the downfall of even the most respected studios. Apparently, assembling a team to do another “Dishonored” was considered to be too much work.

Oh, well.

Publicly held companies face constant pressure to deliver quarterly profits to satisfy shareholders, often leading to cost-cutting measures and a reliance on exploitative monetization tactics. This mirrors the historical resistance of the horse-drawn carriage industry to automobiles in the early 20th century, where businesses clung to outdated models rather than embracing innovation.

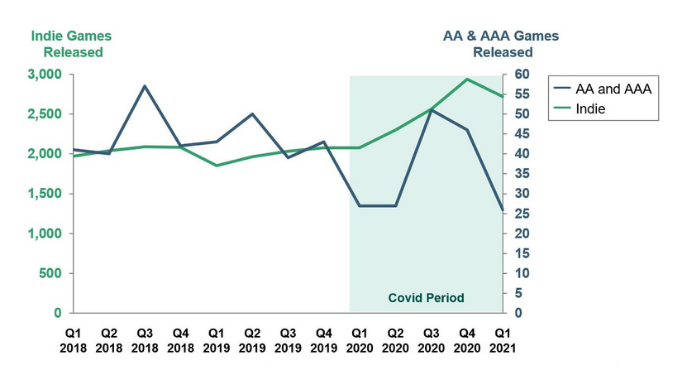

In 2022, indie games accounted for 40% of all game releases on Steam, demonstrating the growing demand for unique and innovative experiences. However, it doesn’t necessarily translate to significant revenue for these developers. Even though large studios may release subpar games, their established brands and marketing budgets often give them an advantage over indie titles in terms of consumer trust and visibility.

The parallels between the tech giants and the gaming industry in their embrace of enshittification are striking. Companies that have achieved significant market dominance are now prioritizing short-term profits over long-term sustainability, often at the expense of product quality and user experience. Just as modern tech companies exploit their captive users by allowing their products and services to deteriorate, gaming giants are increasingly relying on exploitative monetization strategies and the integration of live service mechanics into games that don’t necessarily benefit from them.

The businesses that will endure are those with the vision to relentlessly pursue innovation, even if it means cannibalizing their own profitable legacy products and services.

Or, perhaps, the cycle is broken, and we will transcend destruction.